There’s a very long tradition of writers talking about their characters’ voices. It was, after all, because of that tradition that we ran our study of writers at the Edinburgh Book Festival in the first place. Yet the study is more of a snapshot in time, capturing the similarities and differences between writers at a particular moment rather than across different periods. So in this blog series we’ll take the long view, following the thread as it weaves in and out of history.

In the third instalment of our four part series on the history of writers’ inner voices, John Foxwell writes:

We ended last time with the idea which seems to be at the heart of the creativity debate: that there are two parts of the mind (a ‘controlling’ part and an ‘uncontrolled’ part), and that the production of art involves some kind of interaction between the two. The debate itself is usually around which part is more important, and this in turn is usually related to whatever is considered ‘good’ art at the time.

By and large, the Romantics fall pretty squarely into the ‘uncontrolled’ camp. ‘All good poetry,’ according to William Wordsworth, ‘is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ – and although he tempers this pronouncement a little by saying that it also requires the poet to have ‘thought long and deeply’ on a subject, he ends up coming full circle by saying that thoughts are ‘representatives of all our past feelings’. Similarly, his famous idea of poetry coming from ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’ pretty quickly gets rid of the actual tranquillity:

I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced

(Wordsworth, Preface to the Lyrical Ballads)

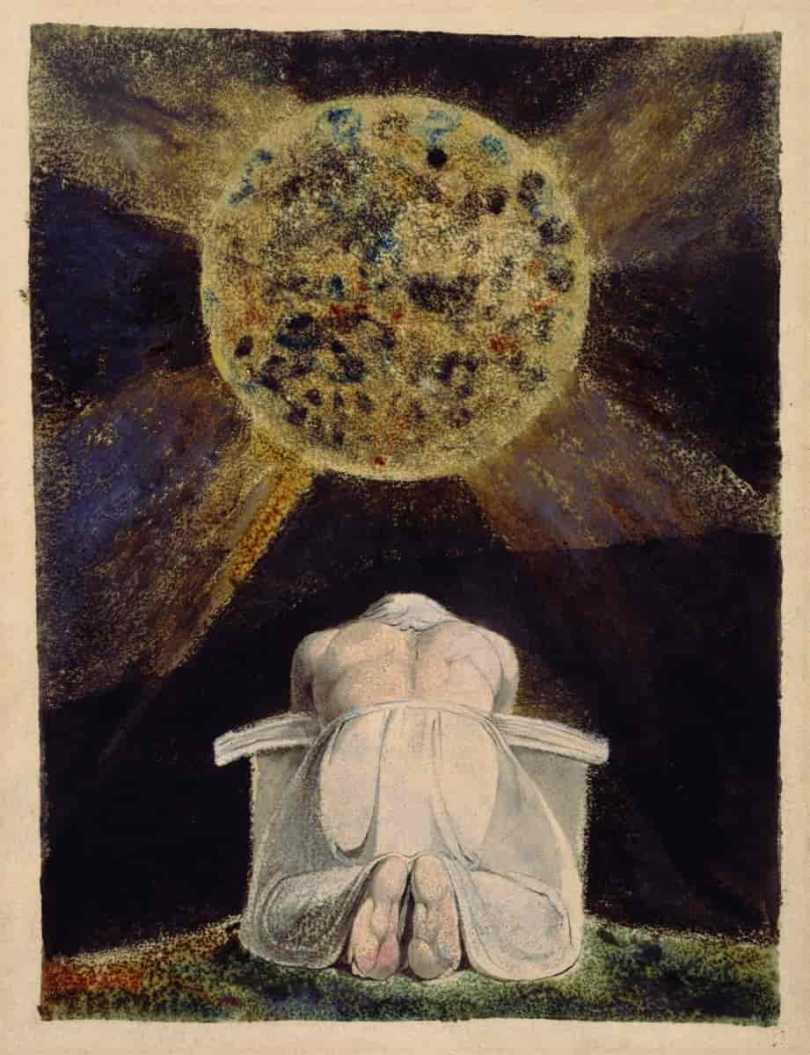

From around the same time, and showing a broadly similar strain of thought, we have William Blake’s excuses for failing to follow his brief for a commission:

I find more and more that my style of designing is a species by itself, and in this which I send you have been compell’d by my Genius or Angel to follow where he led […] At any rate, my excuse must be: I could not do otherwise; it was out of my power! […] tho I call them mine, I know they are not mine, being of the same opinion with Milton when he says that the Muse visits his slumbers and awakes and governs his song

(Blake, Letter to Dr Trusler, Aug 1799)

Samuel Coleridge, meanwhile, has his well-known story of the composition of Kubla Khan, which he claimed came to him in a ‘profound sleep’ during which he composed ‘two or three hundred lines’. In Coleridge’s account,

all the images rose up before him as things, with a parallel production of the correspondent expression, without any sensation or consciousness of effort.

(Coleridge, Prefatory Note to Kubla Khan)

There’s a fairly involved debate around just how true this story is, given that there’s some evidence that Coleridge did in fact make changes to both the poem and the story of its composition. What matters for us here, though, is the way that the story of the composition ended up being an essential part of the poem itself. It’s potentially a major part of how the Romantics shift the overall debate around creativity back to something like its original footing, since the process of composition becomes bound up with the ‘value’ the work is thought to have. Just as the idea of Muses etc. implied that the value of a work was already guaranteed by its divine origin, so the idea of the poem arising uncontrolled from the poet came to be associated with ideas like integrity and ‘authenticity’.

At least, that’s how it all looks in hindsight, and taking a very broad view. It’s worth bearing in mind that it seems like the Romantics didn’t really introduce a new idea of what artistic creation involved. As we’ve seen, the general idea that creativity includes a part that’s somehow outside of the individual’s conscious control has such a long tradition that it’s pretty much built into the language. Instead, it’s more that the Romantics created the impression that the uncontrolled, unadulterated impulse was a more certain guide to artistic merit.

In any case, it’s also with the Romantics we begin to start seeing references to the independence of characters, since the period coincides with the growth of the novel. This growth is as much literal as figurative – not only does the form change, but novels just start getting longer and longer, and thus authors start getting preoccupied with their characters for greater stretches of time. Walter Scott, for instance, includes an ‘introductory epistle’ to one of his novels which presents a dialogue between the Author of the Waverley Novels (i.e. himself) and the fictional Captain Clutterbuck, where the Author describes his experience of writing:

I think there is a daemon who seats himself on the feather of my pen when I begin to write, and leads it astray from the purpose. Characters expand under my hand; incidents are multiplied; the story lingers, while the materials increase; my regular mansion turns out a Gothic anomaly, and the work is closed long before I have attained the point I proposed.

(Scott, The Fortunes of Nigel)

As the Author points out, this makes it rather difficult to plan his novels as carefully as he should like – especially since, in his experience, the more he tries to consciously shape a passage, the less the public appears to like it (at least in comparison to those passages which he writes in a hurry). Again, this seems to fit with the overall Romantic preference. Yet perhaps more importantly, Scott also makes it plain that there’s a personal reason for letting his characters dictate the course of his writing: he gets bored if he’s in complete control. If he ‘resists the temptation’ to follow his characters rather than sticking to the plot, his thoughts become ‘prosy, flat, and dull; I write painfully to myself, and under a consciousness of flagging which makes me flag still more.’

With the Victorian novelists, reports of the freedom of characters are even more pronounced. Like Scott, these writers were under a certain amount of pressure to churn out large volumes of prose at speed to meet their publication deadlines (many novels of the period being published in serial instalments). Anthony Trollope, for instance, is famous for writing with his watch beside him and making sure he wrote ‘250 words every quarter of an hour’. Yet Trollope, perhaps even more than Scott, was committed to realising his characters as much as possible. An author, he claimed, must ‘live with’ his characters:

They must be with him as he lies down to sleep, and as he wakes from his dreams. He must learn to hate them and to love them. He must argue with them, quarrel with them, forgive them, and even submit to them. […] On the last day of each month recorded, every person in his novel should be a month older than on the first.

(Trollope, Autobiography)

Even after having killed off one of his characters in a fit of pique – after hearing a couple of men at his club complaining about her turning up too often – Trollope found that she stayed with him.

It was impossible for me not to hear their words, and almost impossible to hear them and be quiet. I got up, and standing between them, I acknowledged myself to be the culprit. ‘As to Mrs. Proudie,’ I said, ‘I will go home and kill her before the week is over.’ And so I did.

I have sometimes regretted the deed, so great was my delight in writing about Mrs. Proudie, so thorough was my knowledge of all the little shades of her character. […] I have never disserved myself from Mrs. Proudie, and still live much in company with her ghost.

(Trollope, Autobiography)

Charles Dickens also frequently described the independence of his characters, with his own experience being more akin to that of an observer than a creator:

I don’t invent it – really do not – but see it, and write it down… It is only when it all fades away and is gone, that I begin to suspect that its momentary relief has cost me something.

(Dickens, Letter to John Forster, Oct 1841)

As to the way in which these characters have opened out, that is, to me, one of the most surprising processes of the mind in this sort of invention. Given what one knows, what one does not know springs up; and I am as absolutely certain of its being true, as I am of the law of gravitation – if such a thing be possible, more so.

(Dickens, Letter to John Forster, Oct 1843)

As with Trollope, Dickens’ characters did not necessarily ‘leave’ when the novels in which they featured were complete. According to the publisher and poet James T. Fields, Dickens told him that

…when the children of his brain had once been launched, free and clear of him, into the world, they would sometimes turn up in the most unexpected manner to look their father in the face.

(Fields, Yesterdays with Authors)

If we were to leave things here, we might be tempted to draw all sorts of connections between the way these writers were working – churning out vast amounts of material for popular consumption in a relatively short amount of time – and the experiences they describe of the independence of their characters. Yet as we shall see, despite the variations in both production and intended audience that start coming in at the turn of the century, the experience of independent characters continues to turn up all over the place. What we can say instead, perhaps, is that over the course of the 19th Century the ‘uncontrolled’ dimension of the creative process remains very much a part of how writing is talked about – it’s just that it begins to crystallise around characters.

For the other posts in the series, see:

Part 1: The Muses and Classical Literature